The recent rediscovery of the Naacal tablets really should have sounded like a bomb. After all, this is one crucial piece of evidence that has been eluding everyone, except James Churchward of course, for more than eighty years. One could even say that, with time, they had gained a privileged place in the pantheon of enigmatic and elusive artifacts everybody talks about but no one has ever seen.

This time however, things are different. Thanks to the tenacity of German independent researcher, author and travel agency manager Thomas Ritter, we can actually contemplate a couple of photographs which Mr. Ritter’s private and knowledgeable guide kindly allowed him to snap inside the “secret library” underneath Sri Ekambaranatha temple in Kanchipuram, India.

Needless to say, such underground hidden places of knowledge are not just open to anyone, especially not to Westerners. Mr. Ritter, who says he has been visiting India since 1993, however is a regular. Or at least that’s the impression we can get from reading his books and articles about the Indian palm-leaf libraries and the prophecies and predictions they are supposed to contain.

Up until July 2010 however, the “secret underground tunnels” of Sri Ekambaranatha temple had remained closed to him. According to the account he made of his discovery, it was mostly thanks to the “Navagraha ring” he wore, and possibly his personal experience and charisma, that Mr. Ritter finally attracted the attention of a seemingly influential elder, Pachayappa. The latter ultimately agreed to offer him the tour of the forbidden locations underneath the temple and allowed him to bring these few photos back with him.

Reading Mr. Ritter’s account of his visit of the subterranean tunnel system is not unlike watching an Indiana Jones movie. Torch-lit windy tunnels and vast decorated halls, rooms filled with tablets and books in strange unknown writings, spiders crawling in dark corners, all the ingredients of a classic adventure movie are there.

In comparison though, the movie seems more believable. Especially when Mr. Ritter presents us the photographs of the two Naacal tablets he claims to have examined in “chamber no. 4” of the “underground tunnel system”. This should have been the culminating point, the moment where all doubts about the reality of these tablets would have crumbled. In fine, it should have been the revenge of all independent researchers who have been struggling for over eighty years to prove their existence.

Unfortunately, it is not.

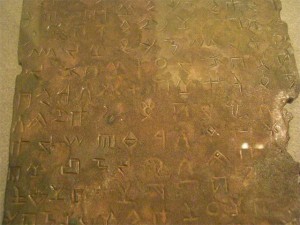

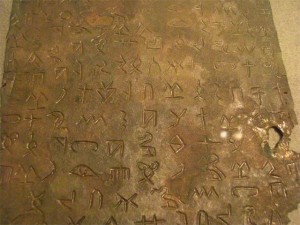

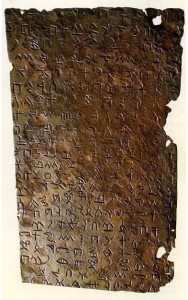

Whoever chose to recycle these pictures as “Naacal” tablets did a poor job. Any knowledgeable researcher in ancient Near-Eastern studies would not only recognize almost instantly the script on these pictures but the tablets themselves. Or, more precisely *the* tablet itself, as both pictures do not represent two distinct tablets but are in fact two close-ups of a single tablet, and a well-known one at that.

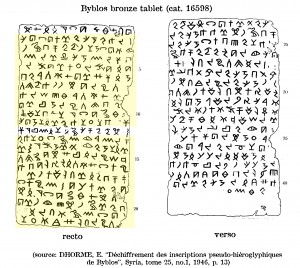

The tablet in question belongs to a series of inscribed artifacts unearthed by French archaeologist Maurice Dunand in the late 1920s and early 1930s in Byblos, Lebanon. The inscriptions on these items have remained undeciphered until now, mainly because of the small size of the available corpus which comprises only ten individual texts. The script however is well identified and has been categorized as a pseudo-hieroglyphic script named Proto-Byblian, which was in use in Byblos during the first half of the 2nd millennium B.C. The two-sided bronze tablet which Mr. Ritter presents us as a “naacal” tablet is held by the Beirut museum (cat. 16598) and has been studied by many scholars in their attempts to decipher the Proto-Byblian script.

A comparison between Mr. Ritter’s photos and the Byblos bronze tablet shows without any possible doubts that they are one and the same.

Byblos bronze tablet. Colored zones correspond to the two pictures provided by Mr. Ritter. (Source: DHORME, E. "Déchiffrement des inscriptions pseudo-hiéroglyphiques de Byblos", Syria, tome 25, fasc. 1, 1946, p.13)

This not only casts more than serious doubts on the credibility of the “rediscovery” of the “naacal” tablets, but also to the story of Mr. Ritter’s visit to Sri Ekambaranatha as a whole. One would now need to explain how a bronze tablet found in Byblos and on display in Beirut could be at the same time in some supposed underground library under an Indian temple. It’s not even a copy of the Byblos tablet we are talking about, this is the same tablet as the one found by Maurice Dunand in the 1930s.

In light of this information, one can only conclude to the fraudulent nature of the rediscovery. If this is a joke, this is a bad one and poorly executed at that.

The problem with such misinformation is that it tends to make legitimate and serious research on James Churchward’s Mu theory more focused on debunking absurdities such as this one and ultimately appear less credible. Let’s not fall for this silly trap and move on to real questions.